Libraries fulfill a special function in society. Library buildings are places of learning, gathering and exploring. People often form strong emotional associations with the libraries in their lives.

Architects approach library projects from multiple perspectives. Who will use the library and how will they use it? How will people get to the library? What collections will the library house? How much can be determined about its future collections? Each of the buildings below is an example of different ways architects have responded to the challenge of designing a library during different periods.

Modernity – Stockholm Public Library versus Viipuri (now Vyborg) Library

Stockholm Public Library (1928), developed by influential Swedish architect Erik Gunnar Asplund (b. 1885–d. 1940), could be the first significant example of its architectural-type featuring a modern intention during the 20th century. Asplund had a dominantly classical upbringing, yet the austerity of the inner and outer facades of the library declares a decidedly modern stance.

The final step towards modernity is clearly taken on Viipuri Library (completed 1935) — now Vyborg Library after the city was taken by Russia during the Winter War in 1940. Designed by Finnish architect Alvar Aalto (b. 1898 – d. 1976), the external appearance of the building has a clear resemblance to other canonical projects of the “heroic period” of modern architecture: (e.g.Bauhaus School Building (1925–1926) by Walter Gropius (b. 1883 – d. 1969) in Dessau, Germany).

Deviating from the standard of the avant-garde architecture of the “heroic period,” the interior of the library’s most innovative feature in how lighting is integral to the experience of reading a book, as if it was being done outdoors. This space can now be visited again after decades of abandon and decay, as it was restored by Alvar Aalto Foundation and opened in 2014.

Post-modernity – Utrecht University Library versus Seattle Public Library

So much has happened in the field of architecture since the “heroic” days of modern masters such as Gropius, Le Corbusier or Mies van der Rohe. Yet their legacy remains strong. In the case of Dutch architect Wiel Arets (b. 1955), this legacy is a style which is clear in his extreme austerity of formal means, often labeled as “minimalism.”

Arets’ project for Utrecht University Library (completed in 2004) is one instance in which he displays his limited spatial palette. The outstanding feature in this building is how he deals with the exterior facade as it was a collection of units, an abstraction of stacked books, expressing the accumulation of objects happening in any given library. Inside, things are completely different. Neutrally colored surfaces — black walls, beige floors — make a background for life and the objects that make this space a library: people and books.

Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas (b. 1944) designed Seattle Public Library (completed in 2004) as an experiment on how to arrange the different uses and rooms that make up a building like a library. Like in many of Koolhaas' projects, the elements used are nothing special and they are even purposefully standard. Yet, the way in which he and the Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA) arrange these “ingredients” goes beyond the status quo, producing new ways to understand the contemporary library — which he has tested since the early days of his practice, in unbuilt projects such as Jussieu Libraries Paris (1992). In the case of Seattle Public Library, by detaching the rooms for “books,” “staff,” “headquarters” and “assembly,” the interstitial space results in both the exterior and interior expression of the building, which opens the usually enclosed character of a library.

Deviating from the standard of the avant-garde architecture of the “heroic period,” the most innovative feature of the library’s interior is how integral lighting is to the experience of reading a book, as if it were being done outdoors.

Deviating from the standard of the avant-garde architecture of the “heroic period,” the most innovative feature of the library’s interior is how integral lighting is to the experience of reading a book, as if it were being done outdoors.

Future – Sendai Mediatheque and Liyuan Library

The physical library has been in crisis for a few decades now because of the dawn of Digital Age. Instead of the “bibliotheque” — a place for books — several institutions since the 1990's have started to rebrand themselves as “mediatheques,” embracing all forms of media (physical and digital). One of the very first attempts to do this was Sendai Mediatheque, a competition in Northern Japan which was won by Toyo Ito (b. 1941) in 1995 and completed in 2001. Instead of tailoring the building for the high-technology of the mid 1990s — which would change many times during the lifespan of the facility — Ito designed a very open and flexible plan in which the structure would concentrate the basic infrastructure for the operation of a building like this, namely vertical circulations and technical shafts. Ito was intelligent in acknowledging the slow pace of architecture and the fast pace of technology, particularly digital.

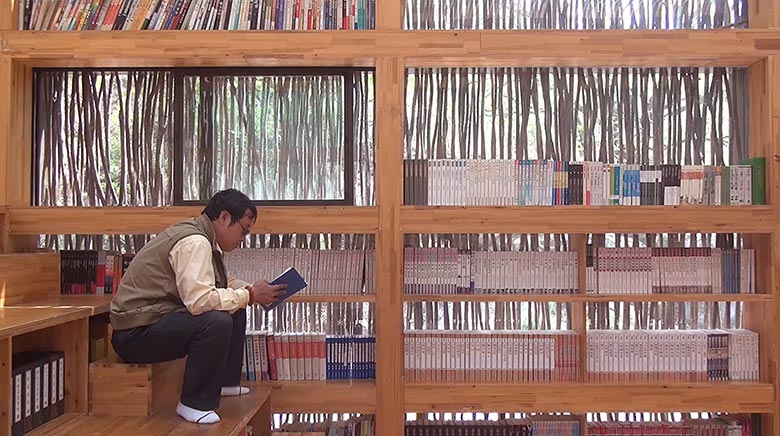

However, not everyone bets on the future as a flux of constant change. Chinese architect and academic Li Xiaodong (b. 1963) designed a finely crafted pavilion in the mountain outskirts of Beijing purposed as a public library for the local community and tourists: Liyuan Library (completed in 2012).

This case is basically a box for books, with natural light coming from all its facades in nuanced ways. One could say this is a temple for books — an old fashioned yet strong gesture of resistance against the potential banality of digital life.

These are only a few examples of library and cultural buildings videos featured exclusively in OnArchitecture, an audiovisual archive for institutions, now available upon subscription at EBSCOhost.

Works Cited

De Ferrari, F., & Grass, D. (Producer). (2009, 24 Dec 2013). Video portrait of Vyborg Library / Alvar Aalto. OnArchitecture Institutional. Retrieved from http://www.onarchitecture.com/works/vyborg-library. Date accessed: 08 Jan. 2019.

De Ferrari, F., & Grass, D. (Producer). (2010, 24 Dec 2013). Video portrait of Utrecht University Library / Wiel Arets. OnArchitecture Institutional. Retrieved from http://www.onarchitecture.com/works/utrecht-university-library. Date accessed: 08 Jan. 2019.

De Ferrari, F., & Grass, D. (Producer). (2014, 24 Dec 2016). Video portrait of Seattle Public Library / OMA. OnArchitecture Institutional. Retrieved from http://www.onarchitecture.com/works/seattle-public-library. Date accessed: 08 Jan. 2019.

De Ferrari, F., & Grass, D. (Producer). (2008, 24 Dec 2013). Video portrait of Sendai Mediatheque / Toyo Ito. OnArchitecture Institutional. Retrieved from http://www.onarchitecture.com/works/sendai-mediateque. Date accessed: 08 Jan. 2019.

De Ferrari, F., & Grass, D. (Producer). (2015, 01 Jan 2015). Video portrait of Liyuan Library by Li Xiaodong. OnArchitecture Institutional. Retrieved from http://www.onarchitecture.com/works/liyuan-library. Date accessed: 08 Jan. 2019.