Not even a week after the Robert E. Lee surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant to end the American Civil War, Abraham Lincoln was assassinated on April 15, 1865. A remarkable letter written by W.R. Batchelder, who was an eye-witness to the murder and captures the frightful chaos, can be found in EBSCO’s digital archives collection. “How can I describe to you,” he asked rhetorically, “the scene I witnessed last Friday evening?” His harrowing account bears quoting in full, and is reproduced below:

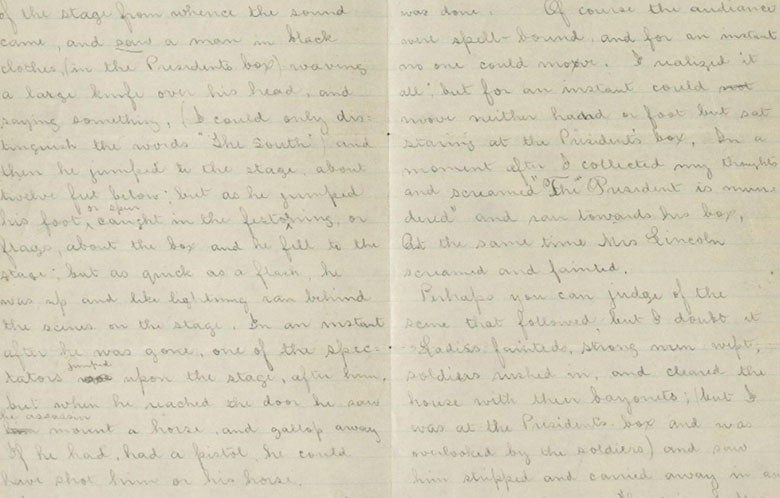

"I was at Ford’s Theatre (Washington) and saw the Murder of President Lincoln. It was a fearful sight, words cannot express the scene. You have undoubtedly read the newspaper accounts which are minutely true. The first I heard, was the crack of a pistol. I thought it was a part of the play, and looked at the part of the stage whence the sound came, and saw a man in black clothes, (in the President’s box) waving a large knife over his head, and saying something, (I could only distinguish the words ‘The South’) and then he jumped to the stage, about twelve feet below; but as he jumped his foot, or spur, caught in the festooning, or flags, about the box and he fell to the stage; but as quick as a flash, he was up and like lightning ran behind the scenes on the stage. In an instant after he was gone, one of the spectators jumped upon the stage, after him, but when he reached the door he saw the assassin mount a horse, and gallop away. If he had, had a pistol, he could have shot him or his horse. It was all done in a minute’s time and cannot be told, as quick as the deed was done. Of course the audience were spell-bound, and for an instant no one could move. I realized it all; but for an instant could move neither hand or foot but sat staring at the President’s box. In a moment after I collected my thoughts and screamed ‘The President is murdered’ and ran toward his box. At the same time Mrs. Lincoln screamed and fainted. Perhaps you can judge of the scene that followed, but I doubt it. Ladies fainted, strong men wept, soldiers rushed in, and cleared the house with their bayonets; (but I was at the President’s box and was overlooked by the soldiers) and saw him stripped and carried away in an insensible state. The cries of Mrs. Lincoln were frightful to hear. Such a scene I never want to be a witness to again. I cannot to this moment realize the fact that it is real, it seems like a dream, to think that he who came in but a few moments before so full of happiness, smiling and waving at the audience who, cheered, stamped their feet, and waved their handkerchiefs, was so brutally murdered. I cannot realize it."

Batchelder’s account was a very personal one – his goal was to relate a shocking and important experience to those who were not there.

But how did the nation as a whole come to make sense of Lincoln’s assassination? The popular media – namely, periodicals and newspapers (but also songs and Lincoln’s funeral procession itself) – helped people process the traumatic event and make greater sense of it.

In fact, Lincoln’s assassination is often credited with, paradoxically, bringing the riven country together after the personal violence inflicted by the Civil War. At the time of his murder, Lincoln was, for a variety of reasons, a deeply unpopular president, having lost the support of even those who had been the most faithful to him. Yet, in the wake of his death, the nation participated in a ritual of collective mourning which brought people together, if not in their opinion of Lincoln, then in their shared grief and suffering.

EBSCO’s digital archives product, American Civil War Periodicals, 1855-1868, contains countless articles chronicling the nation’s mourning of Lincoln. On April 18, 1865, the Army & Navy Official Gazette published information about Lincoln’s funeral cortege, detailing the order of the official procession of military units followed by the civilian procession, including the names of the pall bearers.

In the days that followed, the funeral procession was staged again and again, as the train carrying Lincoln’s body traveled back to his native Springfield, Illinois, for burial. On May 6, 1865, Harper’s Weekly published detailed engravings showing scenes from Lincoln’s life, people gathered around his deathbed, and the funeral procession itself:

"The procession stopped in large and small towns alike, drawing mourners who came to see the body of the fallen president and, as a result, became part of what was a national mourning ritual. Harper’s Weekly estimated that millions came out to see the president’s remains as they traveled from Washington through Baltimore, Harrisburg, Philadelphia, New York, Albany, Buffalo, Cleveland, Columbus, Indianapolis and Chicago. They all shared “their deep sense of public loss, and their appreciation of the many virtues which adorned the life of Abraham Lincoln. All classes,” the magazine reported, “without distinction of politics or creeds, spontaneously united in the posthumous honors. All hearts seemed to beat as one at the bereavement.”

It was not in bringing the Civil War to an end, but actually in his own death, that Lincoln was able to reunite the once divided nation, hearts “beating as one at the bereavement.” Echoing the sentiments of many others, Street and Smith’s New York Weekly wrote on May 11, 1865, “At last there is but one pulsation of the great heart of loyalty; one throb of popular sympathy; one interchange of national emotion!”