There is a rich history of satire expressed through caricature — the deft combination of pointed text and skillfully drawn visual images. The most well-known political cartoonist is perhaps Frenchman Honoré Daumier (1808-1879), who lampooned royalty, political figures, and his fellow countrymen alike. He was famously imprisoned for six months for depicting King Louis Philippe as the literary figure Gargantua, a giant who devours everything in sight.

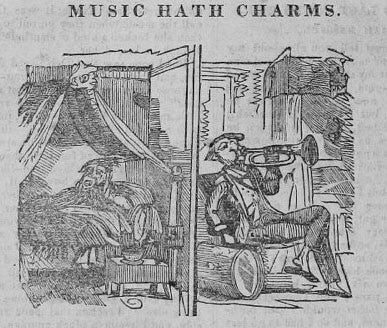

The English, too, were keen satirists, and their comic traditions — especially ribald verse — highly influenced Americans’ comic tastes until the end of the 18th century. Due to the gradual rise in the number of domestic publishers, by the early decades of the 19th century America itself was beginning to establish its own unique satirical tradition. Several magazines were devoted solely to humor targeting both important and mundane subjects. For example, this cartoon from the April 5, 1834 issue of the short-lived magazine Galaxy of Comicalities included a cartoon about noisy neighbors, a perennial problem that persists today:

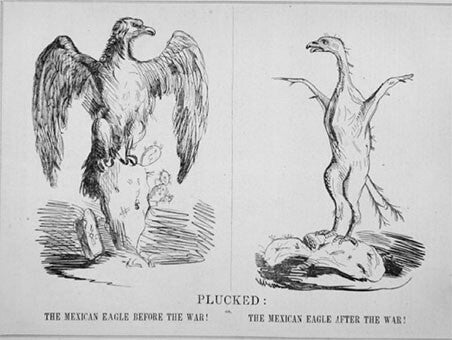

Timely topics were also frequent subjects of the satirical artist’s wit, and in the next decade, the humor magazine Yankee Doodle dedicated many full-page cartoons to the Mexican-American War. This one, published on May 29, 1847, refers to the Americans’ success in several conquests, including the occupation of Chihuahua City:

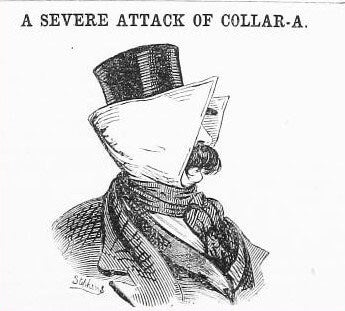

The most effective political cartoons used text and image as economically as possible, whether commenting on war as above, or fashion as below, a cartoon appearing in the April 17, 1852, issue of the Lantern, a comic magazine out of New York City:

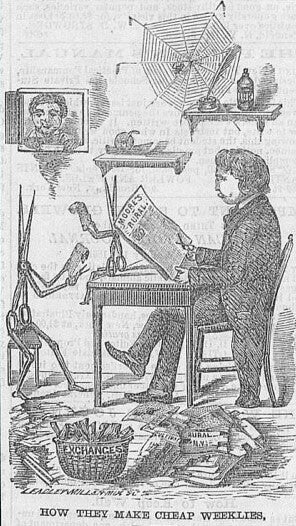

While several mid-century magazines were devoted solely to humor, many other general news and literary publications increasingly found room for jokes, cartoons, and satire within their pages as well. For instance, along with light verse, literature for children, and classified ads, Moore’s Rural New-Yorker included a regular “Wit and Humor” section. The magazine’s artists tackled subjects ranging from the latest economic downturns to the pretensions of the middle classes. The example below, “How They Make Them Cheap Weeklies,” which appeared in the December 8, 1860 issue, is a comment on the plagiarism that was rife within the publishing world. Showing animated scissors busy cutting out articles from magazines like the Rural New-Yorker itself, the cartoon was accompanied by a column decrying the popular practice, describing the editorial process of cheap publications as one involving scissors and shears rather than pen and ink.

American political cartoonists truly found their voice during the Civil War, when they deployed satire to both comment on the unfolding events – and the political decisions behind them – and also to provide the popular reading audience with some much-needed levity during such violent times.

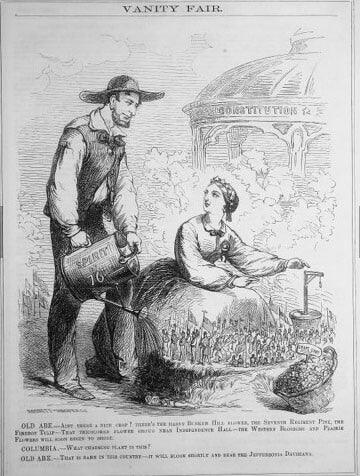

The May 4, 1861 issue of Vanity Fair included a cartoon showing Abraham Lincoln and Columbia (the personification of the United States) tending a garden seeded by Union soldiers, with the hope of growing a “hardy” country in red, white, and blue.

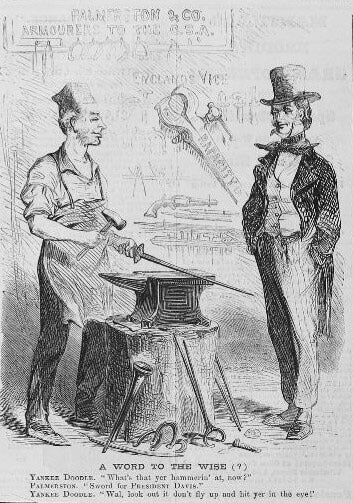

A more pointed example comes from the May 2, 1863 issue of Harper’s Weekly, which carried news of the Civil War as it was unfolding. Yankee Doodle (aka Uncle Sam), cautions a blacksmith against his over-confidence by making a presidential sword for Jefferson Davis: “Wal, look out it don’t fly up and hit yer in the eye!”

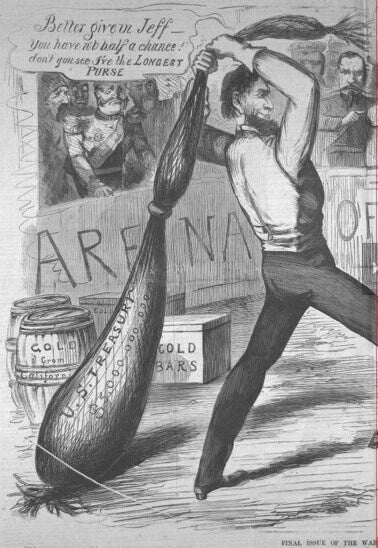

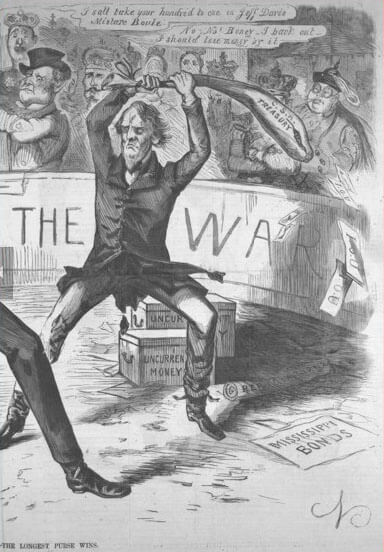

And finally, a complex image showing Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis in the “Arena of War” bludgeoning each other with large purses, with the caption “Final Issue of the War – The Longest Purse Wins,” drove home the point that many believed the North’s victory to be the result of economic rather than military might. It appeared in the March 1, 1864 issue of Frank Leslie’s Budget of Fun.

In these earlier publications one can see the origins of what would become a fully realized vocabulary of satire by the end of the 19th century. The advent of magazines such as Puck and Judge represented the pinnacle of political satire. Printed in full color and featuring lavish political cartoons, they skewered everyone from country rubes to robber barons, important political figures to new immigrants. Thanks to these important precursors, political cartoons are now a staple in every daily newspaper and are commonplace on the web.

[All images taken from The American Antiquarian Society Historical Periodicals digital archives product]