Primary source learning can be a rich, engaging way for students to develop their historical thinking skills. Whether the primary source documents are photos, cartoons, letters, maps or newspaper articles, they can be a springboard for students to dig into different perspectives, analyze and read closely, make connections, infer and — perhaps most importantly — ask questions. As historian David Hackett Fischer eloquently wrote in his 1970 book Historians’ Fallacies Toward a Logic of Historical Thought, “There can be no thinking without questioning — no purposeful study of the past, nor any serious planning for the future.” Indeed, asking questions is one way that students can begin to explore primary source documents with a critical, inquisitive lens while also making connections to the world in which they live. If one of the goals of a social studies education is for students to develop their historical thinking skills and to begin to think as historians and social scientists, there may be no skill more fundamental for students to learn than that of question formulation.

The Question Formulation Technique

The Question Formulation Technique (QFT) is an evidence-based strategy developed by the Right Question Institute that teaches all students how to ask questions about primary sources. The QFT is a simple yet powerful strategy that more than 250,000 educators, from all subject areas and grade levels, are using to teach students how to formulate, work with, and use their own questions to become more curious, engaged, self-directed learners. The QFT provides a space and structure for all students — even those reluctant to participate in class — to inquire. As the authors of the C3 Framework for Social Studies State Standards said, “The QFT allows teachers and students to work with questions in transformative ways as it prioritizes students’ interests and provides a collaborative civic space for curiosity and wonder.” The QFT is also one strategy that can address several domains and competencies outlined in the AASL Standards Framework for Learners, especially for helping learners “display curiosity and initiative” by 1) “Formulating questions about a personal interest or a curricular topic,” and 2) “Systematically questioning and assessing the validity and accuracy of information.” Educators in programs such as the Library of Congress’ Teaching with Primary Sources network have identified how the QFT can support their teaching and have integrated the QFT into their work around the country with much success.

To facilitate the QFT using a primary source document, an educator should first consider which primary source they would like to present to students. In some circumstances, an educator could consider presenting different primary sources to different groups of students, or going through multiple rounds (see example below). The questions students produce on the primary source should align with teaching and learning objectives. It is sometimes helpful to think about which questions students may ask about the primary source and how these may relate to the direction of the lesson.

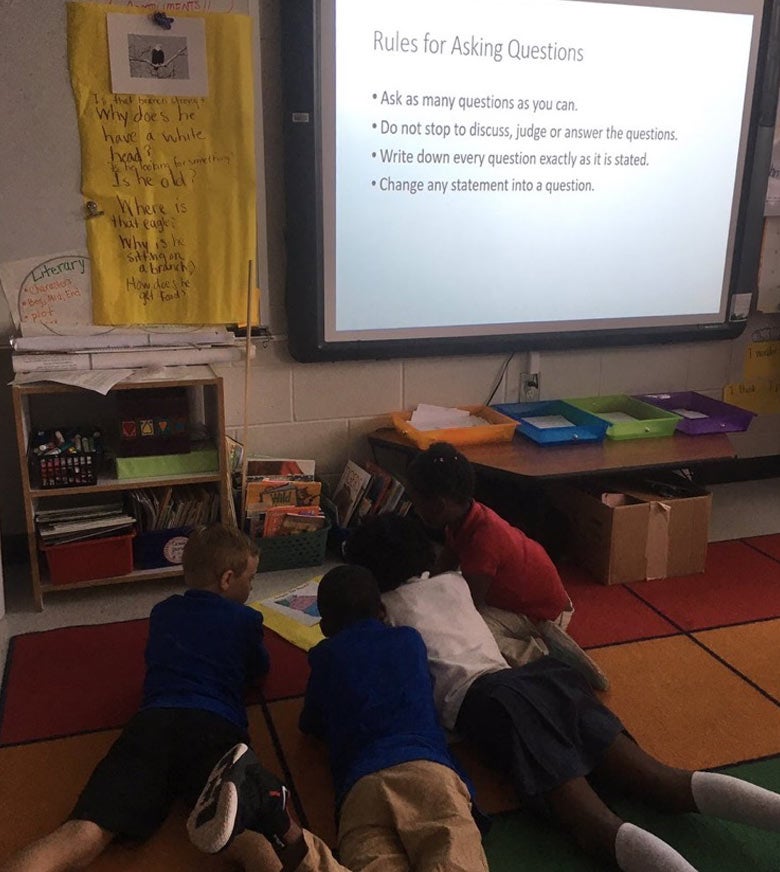

When it is time to facilitate the QFT, the educator will review with students the rules for producing questions:

- Ask as many questions as you can.

- Do not stop to judge, discuss, or answer any questions.

- Write down every question as stated.

- Change any statement into a question.

The educator introduces the Question Focus, or QFocus (a statement, visual or aural aid that stimulates students to generate their own questions). Students quickly move into formulating questions while they follow the rules, and the only sound heard in the classroom is the sound of students’ questions. Following question formulation, students identify different types of questions (open-ended and closed-ended) and the advantages and disadvantages of each. Students learn to reword questions from open to closed-ended and vice versa. Next, the class prioritizes their questions based on instructions provided by the educator (e.g. choose your three most important questions, three questions you would like to research further, three questions that you would like to use to guide your writing assignment). This ties into how the educator envisions students making use of their questions as the lesson progresses. The class then discusses next steps, students reflect on the process of question formulation and what they learned ‘just’ by asking questions about the primary source, and then begin to use their questions in different ways (e.g. write a paper, stimulate a debate, guide research, or develop skills).

By spending time formulating and working with questions on primary sources, students develop civic skills for understanding, thinking, learning, and for life.

By spending time formulating and working with questions on primary sources, students develop civic skills for understanding, thinking, learning, and for life.

Assessing Elementary Students’ Map Skills

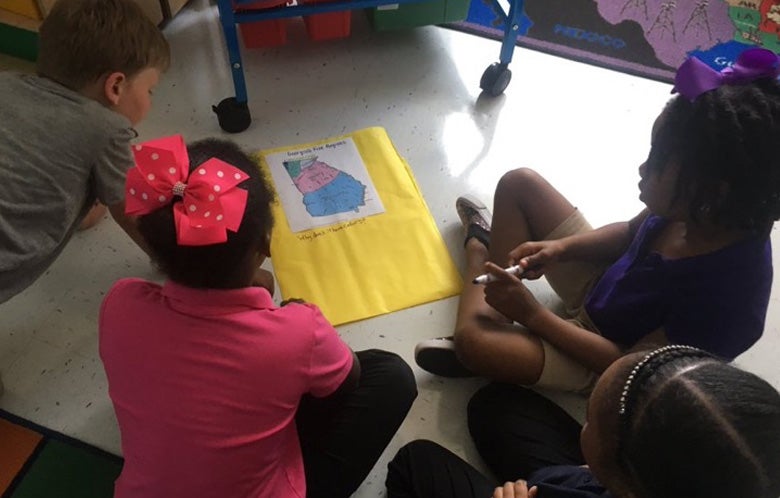

A second-grade teacher at an elementary school in Smyrna, Georgia, used the QFT to launch her unit on Georgia’s geography. Since the teacher was just beginning her unit and it was the students’ first encounter with a regional map, she wanted to pre-assess both their knowledge of the regions and their map skills. This is just one example of how to use a map as a QFocus, but educators can also use other primary source maps (e.g. from the Lewis and Clark archives). Because some of the rules can be conceptual, such as the rule “do not stop to judge, discuss, or answer any questions,” two teachers participated in a mock QFT so that students could monitor how well the teachers followed the rules and see what breaking from the four rules for producing questions may look like in practice. Students particularly enjoyed playing the role of teacher as they learned to identify “judging” and “discussing” questions.

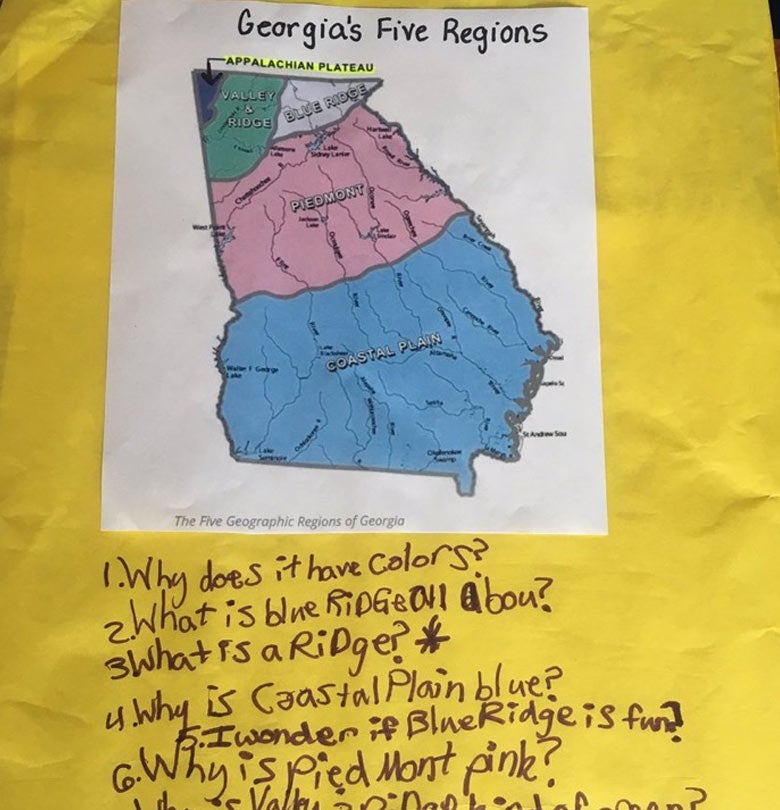

After reviewing and practicing the rules, the teacher introduced the QFocus by describing to students the job of a geographer and how they used maps. She then gave them a physiographic map of Georgia with its rivers as the QFocus (see below) and assigned them to ask questions about the map like a geographer would.

In groups of three, students generated questions and then prioritized them based on which ones would help them better understand the map. Students asked questions such as “Why is the Piedmont pink?” and “Why are there more rivers in the Coastal Plain?” The teacher used the priority questions to guide and differentiate instruction in her geography unit.

Middle School Students Developing Their Historical Thinking Skills

An eighth-grade social studies teacher in Marietta, Georgia, used the QFT during a lesson on American Indian Removal to help students sharpen their historical thinking skills. She used a quote from President Andrew Jackson’s 1830 State of the Union address as the QFocus (see below). Students generated questions, categorized them as open or closed, then conducted a second round of categorization in which they sorted their questions based on four historical thinking skills. They determined which questions dealt with sourcing, contextualizing, close reading, and corroborating; then they discussed why, in the context of this quote, it was important to address these four different types of historical thinking questions. Finally, students prioritized their questions based on which ones would help them best understand why Andrew Jackson would speak about American Indians as he did.

“…the policy of the General Government toward the red man is not only liberal, but generous. He is unwilling to submit to the laws of the States and mingle with their population. To save him from this alternative, or perhaps utter annihilation, the General Government kindly offers him a new home, and proposes to pay the whole expense of his removal and settlement.” ~ U.S. President Andrew Jackson in his Second Annual Message (1830)

To highlight the tension surrounding American Indian Removal, the teacher asked students to use the QFT a second time with a contrasting quote from Chief Justice John Marshall as the QFocus (click link and see second paragraph). As with the QFT process above, the students engaged in an extra round of categorizing to sort their questions by the type of historical thinking skill (i.e. sourcing, contextualizing, close reading, corroborating). They then prioritized their questions based on which ones would best help them to understand why John Marshall would take such a stance in the Cherokee Nation vs. State of Georgia.

By contrasting these two quotes and the questions they generated, students gained a greater appreciation for the value of historical thinking skills while also learning about American Indian history.

Question Formulation: A Foundational Skill

These are just two examples of how the QFT can be used to teach primary sources and develop students’ historical and geographical thinking skills, but there are many more examples (including Question Foci using letters, newspaper articles, images, political cartoons, and photographs) across different grade levels in this downloadable New England Journal of History article. By teaching students how to ask questions, they can begin to drive their learning in new ways as they pose questions to which they would like to learn the answer. By spending time formulating and working with questions on primary sources, students develop civic skills for understanding, thinking, learning, and for life.

EBSCO offers several databases to support primary source learning in K-12 classrooms, including a dozen historical digital archives collections covering art, music, religion, business, education, science, American history, Hispanic history, African-American history, military history and women’s history. In addition, EBSCO offers magazine archives for top publications including TIME, Life, Maclean’s, U.S. News & World Report, Bloomberg Businessweek and People.