Fourth grade students in one Nevada classroom are intently pouring over a 1938 black and white image of the Hoover Dam. All too often, students perceive primary sources like this photograph as indecipherable, dusty artifacts from the past. But these fourth graders are buzzing with excitement and bursting with questions: When was the dam built? How did they build buildings in the water? Why was this dam created? Students are engaged in an activity called the Question Formulation Technique (or QFT for short), through which they are applying an essential skill for primary source investigation that we all have but don’t practice enough: asking questions.

After the lesson, one student reflects that primary sources are important “because you get to have a look at the past and see how it affects the present.” Another student pipes up about getting to “see what people did and their state of mind in the olden days.” As these students demonstrate, primary sources have the unique potential to make stories of our past resonate with us today. The questions we then ask about them further shape our understanding of history and how we connect with it. How can we get all students curious and more deeply engaged with primary sources?

One strategy to try is the Question Formulation Technique (QFT), a simple step-by-step process through which students generate, refine and pursue their own questions. The process, created by the Right Question Institute (rightquestion.org), begins with a short prompt — a provocative statement, quote, image or video — that sets off the initial burst of questions. Primary sources are first-hand accounts, images, satirical cartoons, and newspapers or magazines from the time of an event. Librarians and educators can create natural prompts for student questions using primary sources in EBSCO’s Historical Digital Archives and Magazine Archives collections or in national collections such as those available through the Library of Congress, Smithsonian Libraries and Archives or the National Archives.

While the QFT can be used across grade levels and disciplines to make any content more relevant to students’ interests, it is especially effective for making primary sources more accessible. Students are compelled to think critically and construct meaning like a historian would, by interrogating a source, piecing together context and supposition, and pursuing their own questions. Importantly, the QFT affirms not knowing as a strength and values all the questions students bring to primary sources.

Funded by a grant from the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources program, the Right Question Institute has developed a free, online hub of resources for integrating the QFT with primary source learning. K-12 educators can explore videos, lesson plans, and online learning opportunities to see how questioning primary sources — from kindergarten through high school — can strengthen students’ curiosity, empathy and critical thinking. Here are four ways to get started:

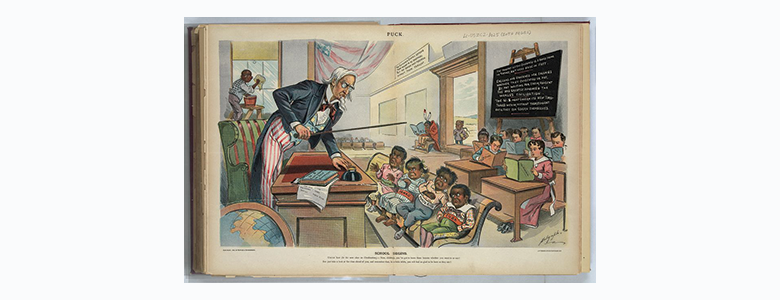

1. Watch videos to hear from teachers and students. Social Studies Instructional Specialist Kim Sergent saw an immediate change when she started incorporating more primary sources into her classroom: “It was no longer me doing all the thinking, but it was the students, and the students became more curious about different perspectives.” Hear teachers like Kim, as well as students, describe how questioning fuels primary source learning in their classrooms. Next watch high school social studies teacher Johnny Walker in action as he facilitates a QFT and primary source discussion with his tenth graders. Students interrogated the stereotypes they saw in an 1899 political cartoon. They asked: “Is the caricature face of the black characters on purpose?” “Why is there an indigenous man sitting in the back?” and “How is this connected to Imperialism?”

1989 satirical cartoon used in a 10th grade QFT lesson plan

2. Check out real lesson plan examples. Tour more than eight different real lesson plan examples and find inspiration for your own work. Spanning grade levels and subject areas, the lesson plans include lesson objectives, outcomes and teacher reflections. Notice where students’ questions below revealed something about their background knowledge or thought process. How would you use these questions to propel the rest of a lesson or unit?

A. Kindergarten lesson

N.Y. Playground, between ca. 1910 and ca. 1915; https://www.loc.gov/item/2014693976/

Questions from kindergartners:

- Where are the boys?

- What are they swinging on?

- Why do those kids have tights on?

- Why is there a truck with hay on it?

- Is this a safe activity?

- Where is the teacher?

- Don’t they have any grass?

- What happens after it rains?

- Why can’t that kid come inside?

- Why don’t they invite that kid to play?

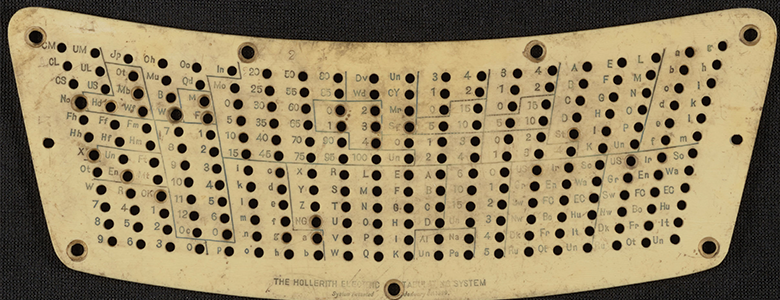

B. High school computer science lesson

Image 9 of Plate, punch card, and instructions for Herman Hollerith's Electric Sorting and Tabulating Machine, ca. 1895. https://www.loc.gov/resource/mcc.023/?sp=9

Questions from high schoolers:

- What is it?

- Why do we need this?

- What is it used for?

- How do you read it?

- Does it work with electricity?

- Who created this?

- How does a punch card work?

- What do the letters and numbers mean?

- Is there a pattern to how the letters and numbers are set up?

- Why are there holes?

- Why is it shaped like that?

- Does this need any other pieces to use it correctly?

- Where do they belong?

- How old is this piece?

- How can they help us today?

3. Learn more on your own time. All educators deserve flexible options to build their own professional learning path. If you find yourself itching for a deeper dive into primary source inquiry, take one, two or all four of the free, on-demand learning modules. You will learn how to use and teach the QFT, how to find primary sources at the Library of Congress, and how to design your own lesson plan. Receive a certificate of completion for one hour of work for each of the modules.

4. Start planning your QFT-primary source lesson. When you’re ready to put the QFT into action with students, download a lesson planning workbook. It’s a comprehensive guide to help you write a QFT-primary source lesson from scratch: Nail down the context and purpose of your lesson, envision the procedure, and design an effective QFocus. You’ll also get a chance to consider how you would ultimately use students’ questions, and room to tailor the QFT instructions for your learners or objectives. For an idea of how you could eventually use student-generated questions to drive the next steps of learning, click through an interactive unit plan example.

All students have the power to tap into their curiosity and study primary sources like historians when given the space to ask their own questions. Head over to the resources hub now to discover how you can make primary source learning deeper, more equitable and more fun for all your students with the Library of Congress and the QFT.