In this series’ first installment on clinician burnout, we examined the challenges created by the rapid and continuing growth of medical information leading to new approaches to its acquisition and application in clinical care. We also considered the contribution of administrative and regulatory burdens on the complexity of care, often leading to both clinician and patient dissatisfaction. Point-of-care (POC) reference tools have had a long history of use. In this second installment, we will explore the evolution of these tools, influenced by both technology and necessity.

During my training in the late 1980’s, accessing clinical information at the POC required published textbooks, condensed references, or colleagues willing to share their insight (what we termed “the curbside consult”). Although extremely convenient, reliance on colleagues is fraught with danger. The veracity of information is often influenced by personal biases, uncertain currency, and at times, well-meaning yet unconscious incompetence. When a question came up, we would often retreat to a clinical workstation to use an assortment of available specialty-specific textbooks.

Carrying these tomes of “authoritative” information from patient to patient was certainly out of the question! Although in general, these references were comprehensive, they weren’t intended for rapid access to information at the POC. They also lacked currency, their evidence-base at least two to three years old at the time of publication. Several of these limitations were addressed using condensed references, not the least of which was that they fit into one’s lab coat pocket; solving the problem of chronic back pain posed by carrying textbooks around. One such example is the Washington Manual of Medical Therapeutics. Although not as broad in scope or depth, it presented information that clinicians most often sought at the POC in a format that enabled more rapid access. Although currency continued to be a limitation, these references were often published more frequently.

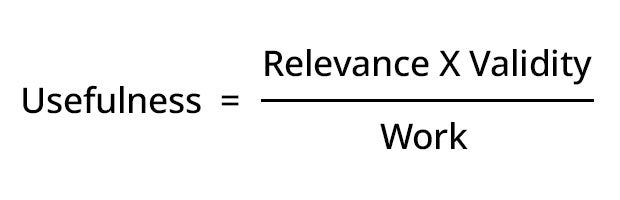

With the evolution of digital technology and the explosion of medical information, numerous POC reference tools are now available on computers or handheld devices of varying breadth, quality, and currency. The value of these tools can be maximized when their creators design them in a manner that supports both their usefulness and use. Slawson and Shaughnessy asserted that the usefulness of POC reference tools depends on the relationship between three variables: relevance, validity, and work. They assert that value increases when the information is highly relevant to the clinician and when the evidence supporting it is accurate and based on rigorous research. A POC tool’s value decreases as the work required to access the information increases.[i]

Designers and authors must address this relationship as they develop these tools. Although they should be comprehensive, the depth of information provided must be weighed against its relevance to the busy clinician at the POC (e.g., provide more “signal” and less “noise”). Reporting outdated, inaccurate, or information based on questionable evidence also diminishes the value of these tools. Tools that provide evidence-based medicine as opposed to “editor-biased” medicine (e.g., opinion) are also of greater value to clinicians at the POC.[ii]

Research has shed light on what queries are most relevant to clinicians at the POC. In two studies examining clinician information-seeking behavior at the POC, they reported the top two categories queried were treatment and diagnosis. [iii],[iv] Esoteric searches were far less common.

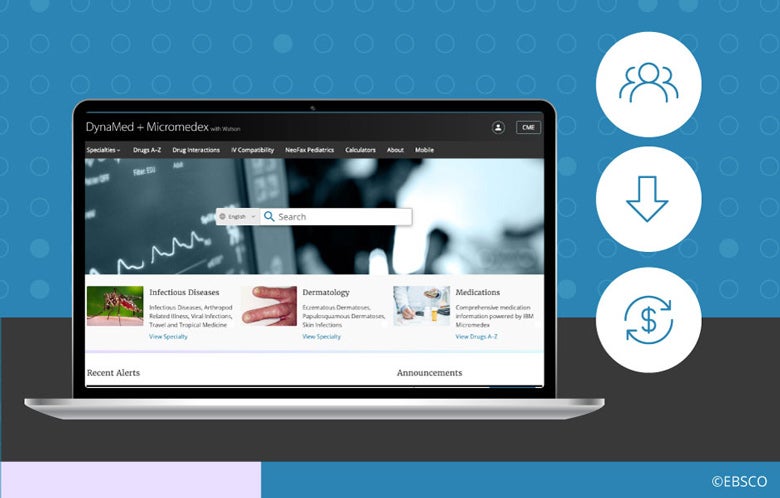

With this understanding, POC reference tools must provide rapid answers to the most sought-after questions. However, they should also enable clinicians to pursue answers to more in-depth questions when they have the time and/or need. DynaMed’s format of “progressive disclosure”, rapidly providing commonly sought-after information in “Overview and Recommendations,” while offering more in-depth information as needed, takes this into consideration.

Information and recommendations made at the POC must be reliable, current, and based on the most rigorous evidence. It is impossible for clinicians to maintain an evidence-based fund of knowledge vetted for statistical rigor in the busy clinical environment in which they function. This is a major strength of these reference tools. All too often, POC tools use dated information that is not carefully vetted or employ recommendations that use clinical consensus or an author’s personal experience. When there is a paucity of evidence, this can be appropriate. However, when it occurs, it should be disclosed so that decisions are made with this understanding.

A POC tool’s value decreases as the work required to access the information increases.

A POC tool’s value decreases as the work required to access the information increases.

The systematic surveillance system used by DynaMed is an example of a system designed to meet these standards. It continually culls the literature for new evidence, evaluates it for relevance and statistical rigor, grades the evidence and rapidly publishes information that makes it through this exhaustive process. Relevant and current information that is statistically flawed should not be what is provided to clinicians at the POC.

Lastly, POC reference tools must be easy to use and should not significantly contribute to workflow disruption for already overburdened clinicians. Ely et al, reported that doctors spent an average of less than two minutes pursuing an answer to a clinical question at the point of care.[v] They concluded that if the information is not easy to find, clinicians will abandon their search and be more hesitant to conduct them in the future. Integration into the electronic health record, straightforward searching algorithms, and information laid out in an easily digestible format are an essential quality of POC reference tools.

Point-of-care reference tools have had a long history, have evolved over time, and have taken advantage of the advancing technology. We have a better, yet still incomplete, understanding of what the ideal POC tool will look like. In the next installment, we will look toward their future; improving on the existing foundation and leveraging the technology to better meet the needs of the clinician.

[i] Slawson DC, Shaughnessy AF. Obtaining useful information from expert based sources. BMJ 1997 Mar 29;314 (7085):947-9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7085.947.

[ii] Personal correspondence with Dr. Richard Loria

[iii] Daei A, Soleymani MR, Ashrafi-Rizi H, et al. Clinical information seeking behavior of physicians: A systematic review. Int J Med Inform. 2020 Jul;139:104144. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2020.104144. Epub 2020 April 18.

[iv] Davies K, Harrison J. The information-seeking behaviour of doctors: a review of the evidence. Health Info Libr J. 2007 Jun;24(2)78-94. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2007.00713.x.

[v] Ely JW, Osheroff JA, Ebell MH, et al. Obstacles to answering doctor’s questions about patient care with evidence: qualitative study. BMJ. 2002 Mar 23; 324(7339): 710.doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7339.710.