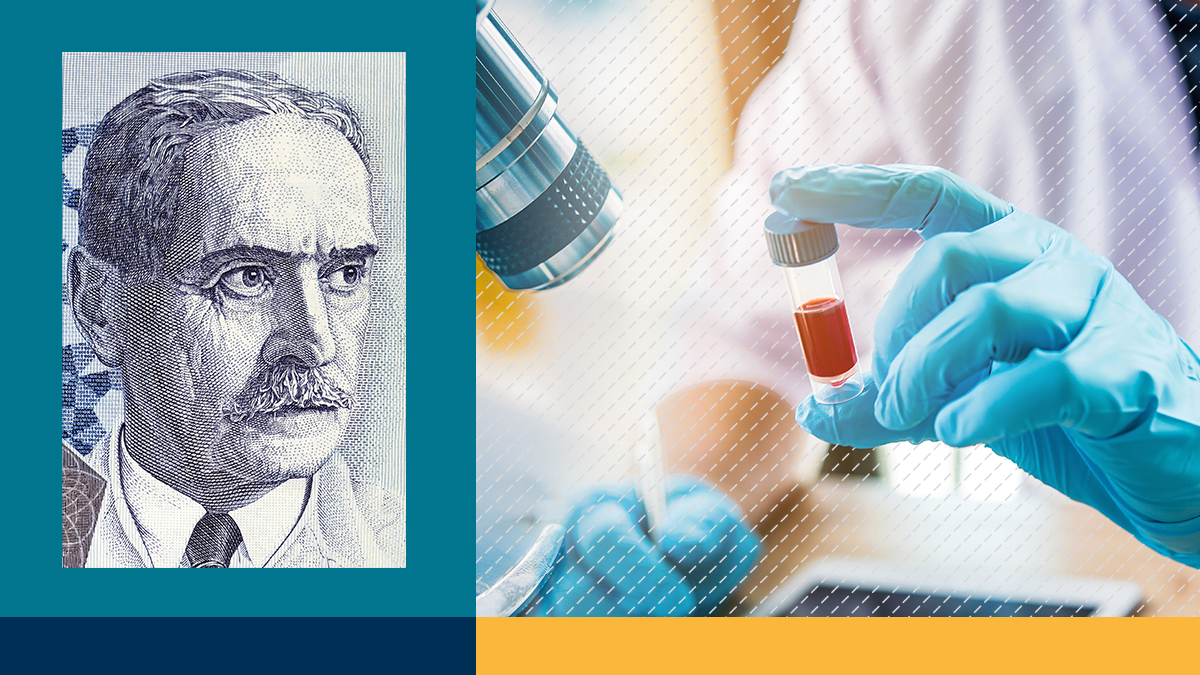

Have you ever heard of Dr. Karl Landsteiner?

Probably not, let me tell you a bit about him.

Dr. Landsteiner is the physician and Nobel Laureate who has arguably saved more than one billion lives. Here are just a few of his many accomplishments:

- Discovered A, B, O blood groups

- Demonstrated that polio was a transmissible agent

- Contributed to understanding immunity to polio that led to the development of polio vaccines

- Demonstrated the development of hemolysins and hemagglutinins when animals are injected with foreign red blood cells

- Discovered cold-agglutinins, elucidating the mechanism of paroxysmal hemoglobinuria

- Elucidated the chemical basis for immune specificity

- Discovered haptens - low molecular weight compounds which are antigenic but not immunogenic

- Developed darkfield microscopy for the detection of the spirochetes of syphilis

- Developed the in vitro culture technique for typhus rickettsia

- Discovered Rh factor (with Weiner), thus elucidating the mechanism of erythroblastosis fetalis (also known as hemolytic disease of the newborn)

In short, Landsteiner was a genius, who despite being just one man, tirelessly worked as though success depended solely on 99 percent perspiration.

When I first read about Landsteiner, I wondered why I did not know more about him. None of my colleagues or students did either. I read a biography by Paul Speiser originally written in German, fortunately translated into English. I discovered archived newspaper articles surrounding his nomination for the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1930. When asked by a New York Times reporter what other applications his discovery of blood groups might have, he answered, ‘I think this discovery may aid in determining the perpetrator at the scene of a crime.’

In fact, in 1903, with Max Richter, Landsteiner had already shown how a blood group could be determined from a sample of dried blood and suggested this could be used in crime-fighting to narrow the list of suspects. Interestingly, when Landsteiner was informed that he had won the Nobel Prize, he was surprised to learn it was for the discovery of A, B, O, blood groups. He thought it should have been for his discovery of haptens and his work on the specificity of the immune response.

I also read his obituary. He suffered a myocardial infarction while working in his laboratory and was hospitalized for days at the Rockefeller University Hospital. He died in June of 1943. When I called the Rockefeller University Hospital to ask about his medical records, I was told that they had been destroyed. I asked the records supervisor to confirm that they had destroyed the medical records of the first U.S. citizen to win a Nobel prize in medicine, there was silence on the end of the line followed by, “yes, I don’t think we knew that.” I replied, “Well, you aren’t the only ones.”

I read that he was survived by a son, Ernst Landsteiner, and (thanks to the internet of the early 1990s) I found that he lived on Cape Cod in Massachusetts. His phone number was listed, so what else was I to do? Followed by, “Hello, you do not know me, you must get tired of these calls. I am a practicing Allergy-Immunology physician in Virginia. I have read about your father. He was a great man and I would love to learn more about him.” There was a pause and Ernst replied, “No one has ever called me about him.” Minutes later, Ernst invited me to visit him on the Cape to talk about his father and to see the remaining Nobel keepsakes he still had.

Ernst himself was a retired Harvard physician, a urologist who had participated in the first kidney transplants. We met over the course of a few days during which Ernst related details surrounding his father’s life. He talked of the accomplishments, but also the struggles, difficulties, and the isolation his father felt. We took the ferry together to visit his father’s grave on Nantucket Island, a place his father loved. I would not see Ernst again, but I am grateful for the time we had and what I learned of his father. There is much more to say about this great man than can be said here.

In a brief biographical memoir, Michael Heidelberger wrote, “The time is past when one man can know all of science. Karl Landsteiner was one of the last possessed of the tremendous intellect that could comprehend and, better still, use practically all of the scientific knowledge of his time.”

We may not be able to master the vast volumes of knowledge such as Landsteiner did in his time, but I am proud to be part of a team at EBSCO that provides clinicians the strongest evidence with practical clinical application in our time.