1. Does sitting in a waiting room near a person with symptomatic COVID-19 put one at “high risk” of exposure?

In the U.S., the CDC still considers people seated in the same waiting room or classroom (six feet away) as a person with symptomatic COVID-19 to be at low risk of exposure. Of course the CDC recommends masks for symptomatic patients in the office and has a checklist handout for providers.

2. Once you’ve had COVID-19, can you get it again?

While it’s clear that patients infected with COVID-19 develop antibodies to the virus, it remains unclear how long the protection lasts. Very early research in macaque monkeys has reportedly demonstrated short-term immunity in primates, but these data have not yet been peer-reviewed. Looking at data from survivors of the SARS (case fatality 11%, 2002) and MERS (case fatality 39%, 2012) epidemics may help us develop a vaccine. Coronaviruses are RNA viruses which mutate rapidly, raising concern that immunity may be temporary (much like why we need yearly flu vaccines).

3. How long can coronavirus remain viable in the air and on surfaces?

SARS-CoV-2 can remain viable in the air for hours and on surfaces for several days. The median half-life of the virus as aerosolized particles is about an hour, but they can remain viable in the air for several hours. In vitro testing demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 can last for up to 72 hours on plastic and stainless steel, up to 24 hours on cardboard, and up to 4 hours on copper. What remains unclear is the viral load required for infection — just because viral particles were identified on cardboard, it is still unknown if the virus can then go on to infect the respiratory tract (NEJM).

4. How do cloth masks compare to surgical masks at preventing transmission of SARS-CoV-2?

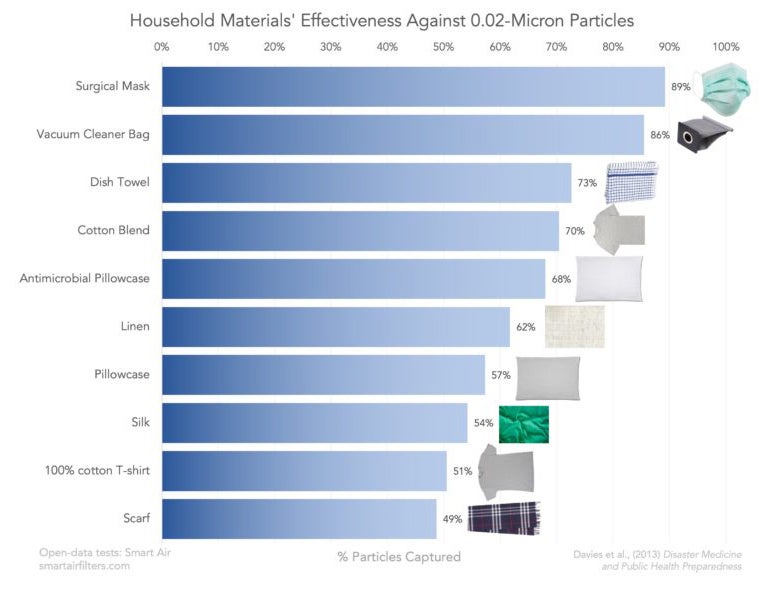

There is little evidence evaluating the use of cloth masks with respect to COVID-19 (estimated size 0.12 microns) specifically. Homemade cloth masks (without filters) may prevent the transmission of some particulate matter but were much less effective than manufactured surgical masks at preventing transmission of influenza (BMJ Open 2015). There is some evidence that certain materials are more helpful than others, however, and perhaps a cloth mask with vacuum bag filter could approximate the efficacy of a surgical mask if it came to that. While these types of masks may not protect the wearer to any significant extent, they may decrease the spread of the virus from asymptomatic persons and limit touching of the face.

5. Will COVID-19 go away when the weather gets warmer?

There is no evidence about whether warm weather will decrease COVID-19 cases, but cases are increasing exponentially in areas of the world that are currently experiencing higher temperatures, such as the American South and Africa. On the other hand, MERS transmission was shown to be partly exacerbated by cold windy weather (BMC Infect Dz), and seasonal factors beyond temperature (such as traditional holidays) have been hypothesized to exacerbate the current COVID-19 outbreak (Swiss Med Weekly, 16 Mar 2020).

6. Does coronavirus affect children?

Yes. Data from China suggest that up to 16 percent of infected children can be asymptomatic. Most children will have only mild symptoms, but a small percentage of children, particularly if they have other underlying illnesses, develop more serious illness requiring intensive care. Children have died from COVID-19 (NEJM 18 Mar 2020 and NEJM 12 Mar 2020).

7. Should breastfeeding mothers not breastfeed if they have symptoms of coronavirus or test positive for disease?

Although we do not know all the facts about how SARS-CoV-2 is spread, it does not appear to be present in breastmilk. Mothers with known SARS-CoV infection or who are under investigation should take extra care when breastfeeding, including washing hands, wearing a mask, and, if possible, pumping milk and having another caregiver feed the infant (CDC, ACOG).

8. Does a negative test rule out infection with SARS-CoV-2?

Keep pretest probability and prevalence in mind when interpreting results of COVID-19 testing. Unless the sensitivity of a test is 100% (and current estimates for SARS-CoV-2 are in the 70-80% range), if prevalence is high and likelihood of disease high, a negative test cannot rule out disease. The possibility of a false negative result should be especially considered if the patient’s recent exposures and clinical presentation indicate that COVID-19 is likely. Given the limitations on testing that have been present, the true prevalence of COVID-19 infection is almost certainly an underrepresentation.

9. Should patients with COVID-19 continue their ACE inhibitors or ARB medications?

SARS-CoV-2 does use angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors to enter respiratory and cardiac cells. Although animal models showed changes in ACE2 expression with ACE inhibitor and ARB use, there are no clinical studies reporting outcomes related to use of these medications. The AHA/ACC currently recommends continuing ACE inhibitors and ARBs given their proven cardioprotective benefits. In addition, there are proposals to use ARBs as a potential co-treatment for COVID-19.

10. Is ibuprofen safe to use during COVID-19 infection?

Although bench science suggested that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may increase ACE2 expression, the currently available evidence suggests ibuprofen and other NSAIDs are safe during COVID-19 infection. Despite initially recommending against NSAIDs, the World Health Organization rescinded that statement and the FDA, along with other organizations, continue to recommend this class of drugs for symptomatic and anti-pyretic therapy.

For more information, see the topic COVID-19 (Novel Coronavirus) in DynaMed.

EBM Focus articles provide concise summaries of clinical trials most likely to inform clinical practice curated by the DynaMed editorial team.