Listen, my children, and you shall hear

Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere,

On the eighteenth of April, in Seventy-Five:

Hardly a man is now alive

Who remembers that famous day and year.

— Opening of “Paul Revere’s Ride” The Atlantic Monthly, January, 1861

Historical letters, diaries, magazines, newspapers, meeting minutes, photographs and more offer the ability to see from the perspectives of those who lived and recorded that history. Many people know about Paul Revere because of the poem, “Paul Revere’s Ride,” that Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote in 1861 to inspire courage to a nation descending into the Civil War, but what else is known about Paul Revere and what really happened that night? Anyone with access to a computer and digital collection access can find out.

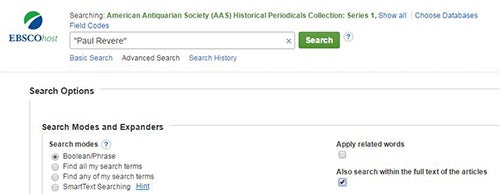

Examining the search results when using the key word “Paul Revere” and activating the “Also search within the full text of the articles” under Advanced Search in EBSCO’s American Antiquarian Society Historical Periodicals Collection reveals that Revere was best known in his time as a skilled engraver, a brilliant metallurgist, and a man of great engineering skill.

“. . . He might be said to hold a sword in one hand, and the implements of mechanical trades in the other, and all of them subservient to the great cause of American liberty. Whenever any thing (sic) new or ingenious in the mechanical line was wanted for the public good, he was looked to for the consummation of the design.” New England Magazine, October, 1832

While Revere did make a deposition to the Massachusetts Provincial Congress in 1775, there is little information about the night until 1792 when Revere wrote a detailed letter, republished in 1832 in the Worcester Magazine and Historical Journal, January, 1826. He writes not only of the ride itself but identifies a traitor in the Sons of Liberty, describes secret meetings at the Green Dragon Tavern, and details his capture by the British:

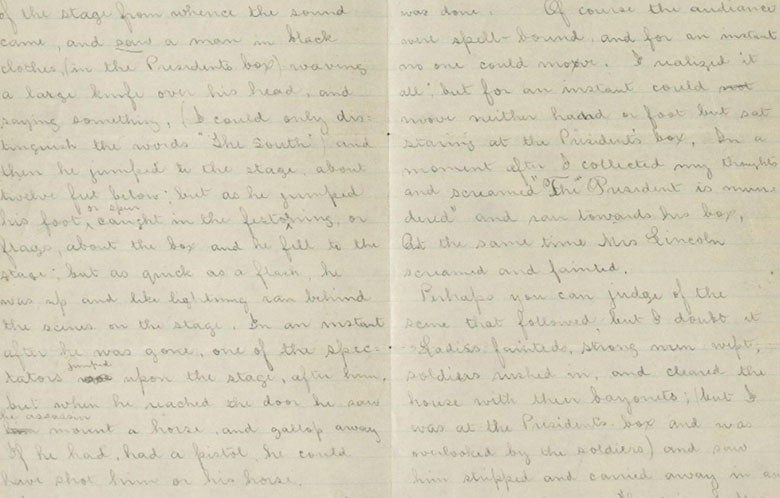

“. . . All five of them came down upon a full gallop; one of them, whom I afterwards found to be a Major Mitchell, of the 5th Regiment, clapped his pistol to my head, called me by name, and told me he was going to ask me some questions, and if I did not give him true answers, he would blow my brains out.” “. . . the Major ordered him, if I attempted to run, or any body insulted them, to blow my brains out. We rode till we got near Lexington meeting house, when the militia fired a volley of guns, which appeared to alarm then very much.”

The soldiers took Revere’s horse for themselves and set him free on foot. He ran and warned John Hancock and Samuel Adams in time for them to get away safely from the soldiers, but returned to Lexington with Hancock’s clerk to retrieve a chest of papers. As a result, they were witness to the fateful shot that marked the beginning of the American Revolution.

“On our way, we passed through the militia. There were about fifty. When we had got about one hundred yards from the meeting house, The British troops appeared on both sides of the meeting house. In their front was an officer on horseback. They made a short halt; when I saw, and heard, a gun fired, which appeared to be a pistol. Then I could distinguish two guns, and then a continual roar of musquetry (sic); when we made off with the trunk.” Worcester Magazine & Historical Journal, January 1826

As lovely as the merits of Longfellow’s poem are, it is Revere’s experiences, told in his own words that will stir the minds of future historians. EBSCO’s newly released, cost-efficient digital primary source collections are available for school libraries to provide students with valuable research skills and the pride of discovery.