Virus evolution is an expected biologic characteristic of SARS-CoV-2, and the longer SARS-CoV-2 is able to persist, the more opportunities it has to evolve. While most genetic variants are of little-to-no consequence, certain attributes could prolong the pandemic and reintroduce risk of COVID-19 even among vaccinated individuals.

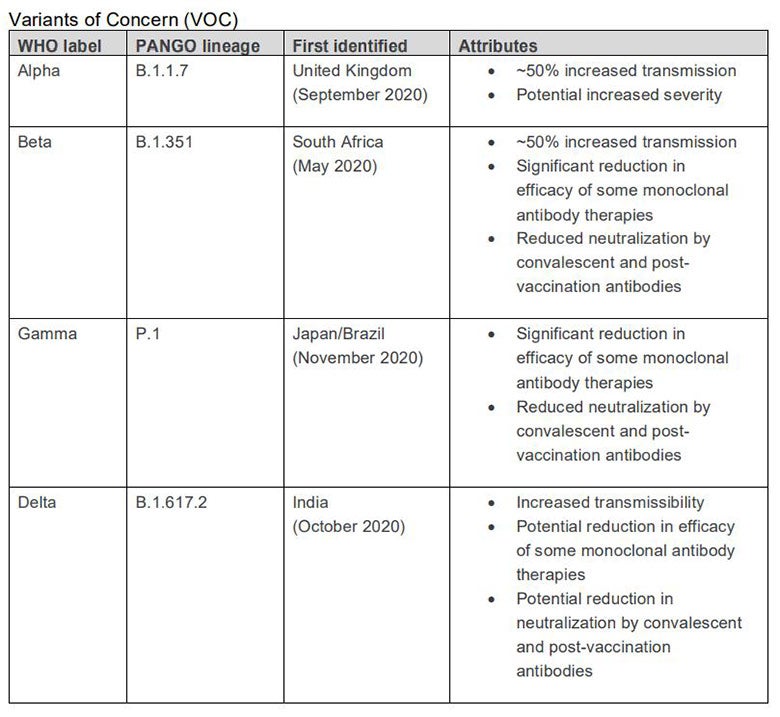

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines classes of SARS-CoV-2 variants based on severity of illness, transmissibility, and their impact on public health and social countermeasures such as lockdowns and masking, and medical countermeasures such as diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccines. Variants of Concern (VOC) are those with evidence of inducing more severe disease, increasing transmissibility, or having an impact on countermeasures. There are currently four VOC identified by the WHO. Variants of Interest (VOI) are those with genetic changes that are suspected to affect transmission, diagnostics, therapeutics, or immunity, but without direct evidence that they do so (yet). Seven VOI are being tracked globally and investigated for potential escalation to VOC. Notably, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) also define Variants of High Consequence (VHC) as variants with clear evidence of significantly reduced effectiveness of medical countermeasures. There are no variants classified as VHC at this time.

Because of the confusing Phylogenetic Assignment of Named Global Outbreak (PANGO) lineage numbering system and various other scientific naming conventions, most variants have been known colloquially by their country of original detection such as the U.K. variant or South African variant, which can be stigmatizing and discriminatory. In response, the WHO assigned Greek letters to VOC and VOI, though research efforts will still include the scientific naming conventions.

Alpha variant: First identified in September 2020, the Alpha variant is currently circulating in 170 countries. It is about 50 percent more transmissible than the original SARS-CoV-2 strain and while there have been conflicting reports, it appears that Alpha may cause more severe disease with greater risk of mortality. However, the Alpha variant is neutralized by therapeutic monoclonal antibodies and antibodies generated after vaccination or recovery from COVID-19, suggesting that the risk of reinfection or breakthrough infection after vaccination is low.

Beta variant: The first variant to be identified in this class in May 2020, the Beta variant was granted designation of VOC status in December. It is associated with enhanced transmissibility and has been detected in 119 countries. Perhaps most concerning is that the Beta variant is associated with reduced efficacy of monoclonal antibody therapy and vaccination. Reinfection after COVID-19 is also possible as neutralization by convalescent serum is reduced.

Gamma variant: There is some debate over whether the Gamma variant is associated with increased transmissibility. However, Gamma is able to evade neutralization by antibodies (monoclonal therapies and those induced by SARS-CoV-2 infection or vaccination), increasing the risk of reinfection and breakthrough infection.

Delta variant: The newest variant to be escalated to variant of concern status is the Delta variant. This variant was responsible for India’s devastating second wave and contributed to prolonging lockdown restrictions despite widespread vaccination in the U.K. Due to its increased transmissibility and reduced efficacy of infection- and vaccine-induced antibodies, it is expected to become the dominant strain globally.

Global vaccination –– as quickly and broadly as possible –– remains the most important pandemic countermeasure to bring case numbers down and restrict the evolution of new variants. Public health and social measures including lockdowns and masking are still needed in certain areas and maybe reinstituted in locations with new community spread of variants. Booster vaccines that target variant strains are currently being investigated, but whether they will be needed (globally or locally) remains unclear. Global genetic surveillance remains essential to track the spread of existing variants and to identify new variants for evaluation.